One of the headline measures announced in this year’s Autumn Budget was the scrapping of the two-child limit in Universal Credit.

Framed by the Labour government as an essential measure to lift 450,000 children out of poverty and reverse long-term NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) trends, this policy shift represents one of the most significant changes to the welfare landscape in a decade.

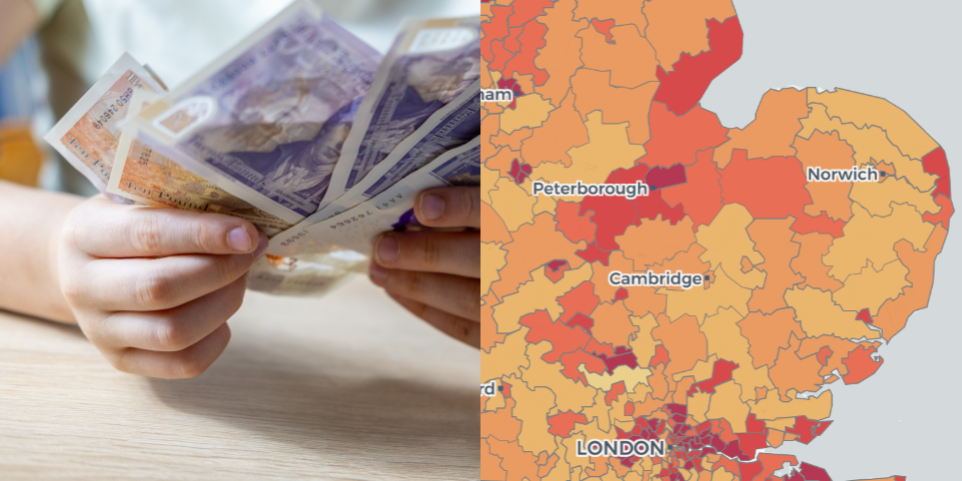

But for organisations in the public and third sectors, the headline number is only half the story. The real story is where this change will be felt. At Polimapper, we have been digging into the data to understand the geography of this decision.

Understanding the two-child limit

Introduced in April 2017, the two-child limit (often called the ‘two-child cap’) restricted the child element of Universal Credit and Tax Credits to the first two children in a household.

For any third or subsequent child born after that date, families would not be eligible for additional support, which would equal approximately £3,500 a year. The policy was originally designed to incentivise work, yet data shows that 59% of affected families have at least one working parent.

Key statistics underpinning the decision include:

- 651,300 households are currently affected by the limit.

- 1,665,500 children live in households impacted by the cap.

- 600,000 people are projected to be lifted out of relative low income by 2030 following the scrap.

- 2 million children will live in households with increased income by 2030 due to the policy change.

The removal of the two-child limit will take place across Great Britain, with the government also funding the Northern Ireland executive to remove the cap should they choose to.

Localised impact of the cap

The Polimapper data team has conducted an in-depth analysis to uncover the localised impact of the benefit cap across Great Britain. Using insights from the Department of Work and Pensions and StatXplore, we calculated which areas have the highest rates of Universal Credit (UC) households not receiving the child element, as well as the total funding families were not eligible for due to the limit.

In April 2025, the constituency of Hackney North and Stoke Newington recorded the highest rate of UC households not receiving a child element, at 11.5%. In total, households in this area would have received an additional £685,000 in support in April if the two child limit was not in place.

Other constituencies with high impact rates include:

- Bradford East: 11.5% of UC households, totalling £732,025 unrealised support

- Luton North: 11.4% of UC households, totalling £424,575 unrealised support

- Birmingham Hodge Hill and Solihull North: 11.3% of UC households, totalling £770,090 unrealised support

- Bury South: 10.9% of UC households, totalling £377,724 unrealised support

In terms of absolute numbers, Birmingham Ladywood and Birmingham Hodge Hill and Solihull North saw the highest volume of affected households, with over 2,600 families in each constituency not receiving the child element.

Conversely, the constituencies of Brighton Pavilion, Kensington and Bayswater, and Hove and Portslade were among the least affected, with only 3% of UC households not receiving the child element.

Additionally, the constituency of Bath recorded the highest rate of affected households qualifying for an exception (12.5%). Exceptions are granted under specific circumstances, such as multiple births (e.g. twins) or adoption.

The table below summarises the figures by nation:

The progress and the challenges that remain

According to the Autumn Budget policy paper, the abolition of the two-child limit is projected to drive the largest reduction in child poverty over a single Parliament since comparable records began. Yet, while charities and third-sector organisations have hailed the decision as a “landmark moment,” they also emphasise that this measure alone is not a silver bullet for tackling poverty across the UK.

The Childhood Trust noted that while the removal will provide “significant relief,” much more is required to meet the Government’s ambitious targets. Crucially, the sector warns that the impact of this policy shift will be uneven. As our data analysis demonstrates, geographical disparities remain stark.

Consequently, organisations continue to lobby for a broader strategy, including enhanced provision for free school meals, affordable housing, and childcare.

Moazzam Malik, chief executive at Save the Children UK: “We welcome this bold action by the Chancellor to scrap the two-child limit. […] We look forward to working with the UK Government to build on this announcement and the forthcoming child poverty strategy to tackle issues that hold too many families back.”

Lynn Perry, chief executive at Barnardo’s: “This is a landmark moment. It’s a moment that could transform life chances for a generation of children. […] However, with one in three children growing up in poverty, there is still much more to do. We urge the government to be even bolder by lifting the benefit cap, which limits the support available to some of the families who are struggling the most.”

Alison Garnham, chief executive at Child Poverty Action Group: “Scrapping the two-child limit will be transformational for children. This is a much-needed fresh start in our country’s efforts to eradicate child poverty and while there is more to do it gives us strong foundations to build on.”